I’ve selected 13 books from those I read in 2016 as the titles I would most like to urge on strangers. Not a “best book” list, nor a “recommended reads” list, in the sense of “this is what you must read to ensure the survival of Western Civilization,” or “drop the names of these titles at your next book discussion,” or “read these books to achieve inner peace.”

I’ve selected 13 books from those I read in 2016 as the titles I would most like to urge on strangers. Not a “best book” list, nor a “recommended reads” list, in the sense of “this is what you must read to ensure the survival of Western Civilization,” or “drop the names of these titles at your next book discussion,” or “read these books to achieve inner peace.”

Rather, these are the books I read last year, both pleasant and unpleasant, that most prompted me to think and feel, and most opened out my ways of looking at the world. Certainly well-written, but more than that, sources of fresh meaning. Unique to me in that sense, and I hope unique to others too.

In rough order of the enthusiasm with which I urge them, with the most enthusiastic saved till last, and keeping in mind that I’m enthusiastic about every one.

13. Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, The Dead Mountaineer’s Inn: One More Last Rite for the Detective Story

13. Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, The Dead Mountaineer’s Inn: One More Last Rite for the Detective Story

I hope the Strugatsky bros had as much fun writing this as I had reading it. Begins as a send-up of the classic puzzle detective novel,then abruptly morphs into an alien contact tale. A little more foreshadowing would have been welcome, though I guess the subtitle ought to be enough.

12. Helen Hunt Jackson, Ramona

This blockbuster from the late 19th Century, deliberately patterned after ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin,’ is set against the racist usurpation of Native American and Hispanic residents of the southern California ‘frontier’ by immigrant whites. ‘Ramona’ single-handedly launched the motifs and mythology of the southwest, and is well worth reading as a crucial cultural artifact.

The doomed romance of the impossibly noble Native American Alessandro and the impossibly beautiful, emotionally flawless Ramona, set against the sere California landscape, is the epitome of cross-cultural melodrama, and in its purity earned my reluctant respect; I must say that ‘Ramona’ grew on me. The portrayal of the majority of the white immigrants as feckless, brutal, and arrogant is cruelly prescient, and the bitter-sweet conclusion tempers the romantic excess.

11. Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

11. Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism

Slavery in the antebellum south as a ferociously cruel application of the capitalist principle of creative destruction, in which the north was fully complicit. Baptist replaces the halcyon, agrarian fantasy of plantation life with case studies and statistics that document the industrial reality through which steadily increased productivity was wrung from Negro “hands”: not plantations, but inhumanly technological slave camps.

A difficult but essential corrective to the soothing myths of American history. Baptiste has been faulted for his single-minded focus on slavery as the engine of the economic growth and prosperity of the early United States, but this criticism does not shade his impassioned portrayal of the human costs.

10. Manuel DeLanda, Assemblage Theory

10. Manuel DeLanda, Assemblage Theory

This is for my library colleagues. I have long thought of a library collection as a gathering of fundamentally unique though formally similar objects, more like a temporary sand castle on the beach than a shelf of identically classified cereal boxes in a grocery. I have characterized this phenomenon as “heterogeneous granularity.”

Now comes Manuel DeLanda to explicate what for me has been a vague notion, outlining the ontology and practical implications of “assemblage,” an organizing principle crossing disciplinary boundaries that he borrows from Deleuze and Guattari, expands upon, and begins to codify.

9. Cixin Liu, The Three-Body Problem

Layers within layers. History and politics, the Cultural Revolution and its residual consequences. First contact, with aliens so different they are literally indescribable. Hard science, from unfolding protons and quantum entanglement to the titular three-body problem. Science fiction based on climate science, threatening the ultimate, suicidal expression of eco-terrorism. Interplanetary espionage. Special effects that culminate in slicing a supertanker and its crew into horizontal layers. A plot that careens between intimate human relationships and rousing space opera.

Most memorably, a firmly non-Western take on a reputedly insular genre.

8. Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

8. Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

In 1993 Octavia Butler imagined an anarchic dystopia, brought on by ecological disaster, that we are well on our way to creating in fact.

This novel and its successor, Parable of the Talents, should be even more required reading than such white-person classics as 1984 and Brave New World. It is a crucially more inclusive rendering of the human costs of our political and social trajectory, told by a black, psychosomatically disabled young woman who ruthlessly forges a unique and touchingly fanatical religion out of the collapse of the everyday world.

7. Paul Kingsnorth, The Wake: A Novel

7. Paul Kingsnorth, The Wake: A Novel

A prose poem of savage power, chronicling the subjugation of the Anglo-Saxon English after the Battle of Hastings, as experienced by a fatally hubristic, abusive freeholder whose rough but settled way of life is destroyed as the Norman invaders extend their rule. Written in a constructed dialect that evokes the cadences, orthography, and vocabulary of Old English but is still understandable (after a few-score pages and with the help of a brief glossary).

I can’t think of an example of “historical” fiction that rivals this book’s potent language, beauty, and depth of alien world-building; there is a haunting subtext involving the old Anglo-Saxon deities, spirits of land and water, forsaken by the duplicitous words and books of the new Christians.

6. Georges Simenon, The Mahé Circle

6. Georges Simenon, The Mahé Circle

The sensuous weight of physical reality corrupts a lonely, conventional provincial physician. A terse masterpiece.

Not your father’s science fiction. Begins nowhere, travels with just-beyond-the-field-of-vision dream logic through a dark, portentous hellscape, returns to where it began. Not to be missed, but takes getting used to and is very, very long.

4. Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend: Neapolitan Novels, Book One

4. Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend: Neapolitan Novels, Book One

Two poor but gifted girls, best friends and sometime adversaries, come of age in the shabby environs of a close-knit Naples neighborhood. Tolerant, hard-edged and realistic, with a disarming humor that takes you unaware, and an uncanny recall of how it is to be young.

3. László Krasznahorkai, Satantango

3. László Krasznahorkai, Satantango

A training manual for the end of days. Organized by the back and forth of the eponymous Satan’s tango–a duplicitous masquerade always ending in betrayal–each of the rain-soaked 12 sections is a single, effectively endless paragraph. Over the course of two gray days, the drunken, feckless detritus of a forgotten Hungarian village make insincere love, argue, joke, dance, drink, and pursue comically, tragically futile obsessions. Satan, it turns out, is other people.

The source for a universally acclaimed seven hour movie by Hungarian director Béla Tarr, which I have not seen. (Drop me a line if you would like to join me for a screening; I imagine Ms. K. will politely decline.) I suspect that both the novel and the film will grow in stature as foundational documents tending toward the apocalypse.

2. Anton Chekhov, The Essential Tales of Chekhov

2. Anton Chekhov, The Essential Tales of Chekhov

Unsparing but compassionate stories that are as moving and fresh now as when they were written, more than a century ago. The pure essence of storytelling.

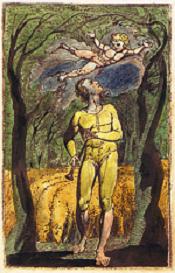

1. William Blake, Songs of Innocence and Experience

1. William Blake, Songs of Innocence and Experience

One of my goals for 2016 was to read Blake’s illuminated poems in the form he created them, page by hand-lettered, hand-colored page. Multiple high-resolution facsimiles are freely available on the web. I began chronologically, and after a few difficult but rewarding weeks, I had progressed from “Songs of Innocence”(1789) to “The Song of Los” (1795). Not particularly impressive if measured by page count (as all right-thinking children’s librarians do).

At this point I paused, reconnoitered, and came to the decision that committing to all of the illuminated poems in a single year was precipitous, presumptuous, and — most alarming — might lead me away from Blake forever. So I postponed until 2017 my entry into the convoluted world of Blake’s epic narratives. This year I take (or at least start) the mystical path to “Jerusalem”: newly acquired lexicons, annotated editions, and guidebooks close at hand.

Of course, what matters is not decoding Blake’s mythology, but the brute, translucent elegance of the illuminations integrated with Blake’s hand-written words: Blake experienced as Blake intended. Last year the few short poems of “Songs of Innocence and of Experience,” which I had previously encountered as text only, came alive in their original form as ecstatic distillations of pure, sensuous experience, to which I have returned again and again. These works of art are simple, direct, and new once more, every time I encounter them.